|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

THE ICE AGE FLOODS MYSTERY |

BRETZ AND PARDEE – SOLVING THE ICE AGE FLOODS MYSTERY | ||

|

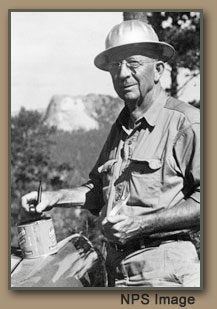

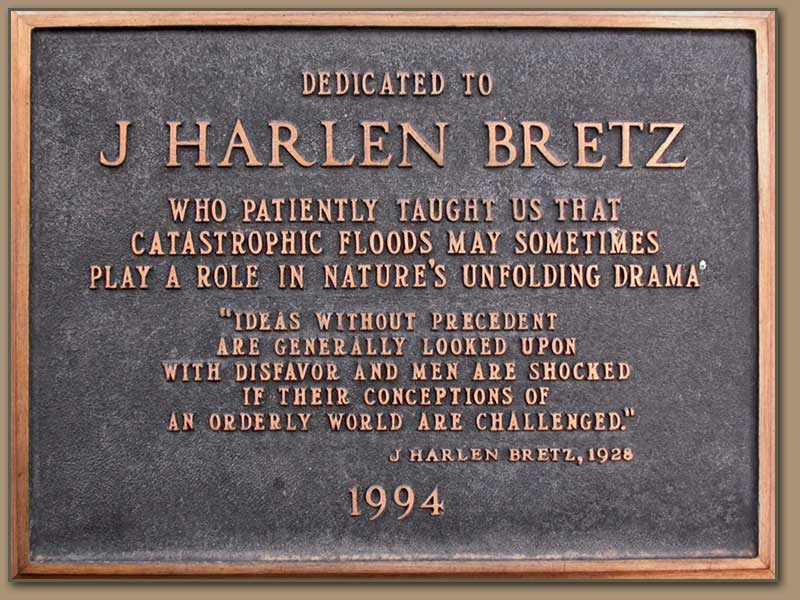

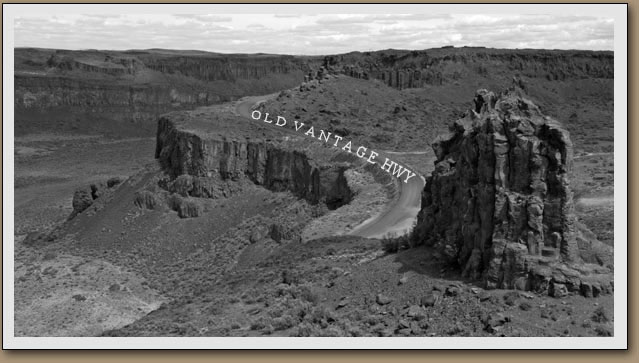

Determining what caused the Columbia Basin’s weird landscape of scablands and coulees generated four decades of bitter scientific controversy. If modern high-resolution aerial photography had been commonplace in the 1920s, the issue might have been resolved quickly and amicably. Instead, geologist J Harlen Bretz had to persuade his critics the hard way. A high-school biology teacher in Seattle whose interest turned to geology, Bretz authored papers on the geology of the Puget Sound Area. After gaining a doctoral degree in his new-found vocation, he briefly served on the University if Washington geology faculty and then joined the faculty of the University of Chicago. Bretz’s brief stint at the U. of W. prompted him to explore the landscape of the Columbia Basin of eastern Washington. What he observed intrigued him—and then amazed him. The massive Dry Falls complex of abandoned waterfalls in Grand Coulee drew his attention, as did what appeared to be potholes in the streambeds of Quincy Basin. For several years he painstakingly explored this strange countryside, often accompanied by his students during summer breaks from his teaching duties. This was the era before GPS devices, quality aerial photos, high-tech measuring devices, computer simulations, pocket calculators—or even paved roads in much of the Columbia Basin.

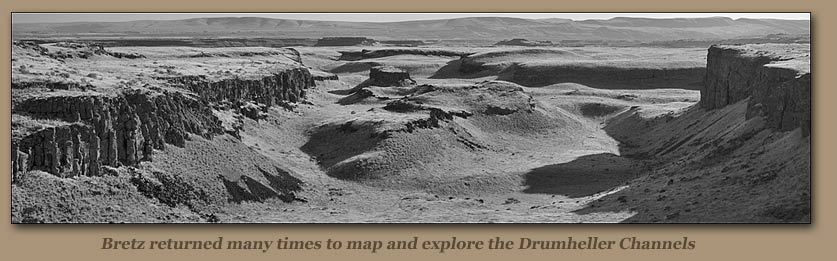

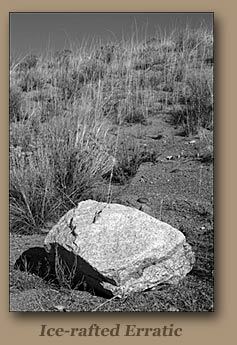

SCABLANDS AND THE “SPOKANE FLOOD”The more he trudged the scablands and coulees, the more evidence he gathered. Granite boulders in Quincy Basin that didn’t belong there because granite is not native to the region. Other “erratic” boulders in the Columbia River Gorge. So-called “hanging valleys” which defied the geologic principal that streams flow together at uniform elevations. Gravel bars at places and elevations where normal erosion processes would not have deposited them. Finally, the scablands lacked the drainage patterns common to valleys created by gradual erosion.  |

| |

| ||

|

In research papers published in 1923 Bretz concluded that the scablands were channels, and not valleys. [Hence his name the “channeled scablands.”] The crazy network of channels, buttes, and canyons in the Columbia Basin could only have been a flood conduit. In addition, the only way these out-of-place “erratic” boulders could have been moved hundreds of miles was to have floated there in rafts of glacial ice. For that to happen the water must have been deep, fast-flowing, and in immense volumes. What Bretz called the “Spokane flood”—a single cataclysmic episode—had produced the scablands, he argued. His findings troubled him in two ways. Like all geologists of his era Bretz had been trained in the doctrine that the landscape is shaped by slow processes. Notions of radical changes or catastrophic occurrences were rejected out of hand. It was a reasonable attitude, but after much study and soul-searching, Bretz had decided that traditional theories of geology could not explain what had happened in the Columbia Basin. Secondly, he knew a flood had occurred, but didn’t know what could have caused it. |

| |

THE 1927 CONFRONTATION | ||

|

The controversy erupted in 1927 when Bretz delivered a presentation to the Geological Society of Washington, D.C. The audience was packed with eminent geologists who were prepared to disagree. Bretz stated his conclusions—and his reservations. His theory was denounced as “preposterous” and “incompetent”. Regrettably, then—and for years after—many of Bretz’s opponents never bothered to visit the scablands, or even undertake a detailed analysis of the evidence he presented. Among that Washington, D.C. audience was Joseph T. Pardee, who apparently whispered to a friend: “I know where Bretz’s flood came from.” Born in 1871, Pardee had studied mining and chemistry at the University of California at Berkeley. In Montana he had operated an assay office and small pacer mine, and later bought a farm in the Bitterroot Valley. As a geologist with the U.S. Geological Survey, Pardee studied the deep valleys of western Montana in order to confirm the existence of a vast glacial lake known as Lake Missoula. He published a report on the subject in 1910. Pardee remained silent at the Washington meeting. To have joined the debate with information favorable to Bretz’s position might have brought on professional suicide because Pardee’s superiors were among the harshest critics of the catastrophic flood theory. At the time Pardee was involved in other projects, and only revisited his Lake Missoula studies a decade later. | ||

PARDEE’S NEW EVIDENCE…AND BRETZ’S VINDICATION | ||

|

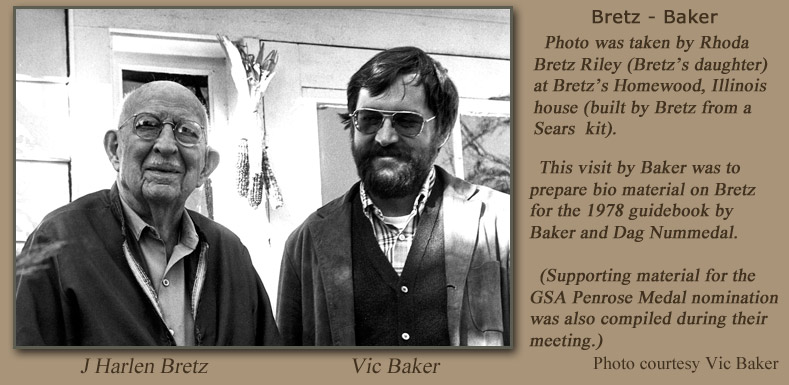

In 1979 Bretz was awarded the Penrose Medal of the Geological Society of America, the most prestigious award in the field of geology. He was 96 years old at the time. After receiving the award, he reportedly told his son:"All my enemies are dead, so I have no one to gloat over." Bretz died in 1981 |

|

John Soennichsen's biography of J Harlen Bretz was published in 2008. |

NEW: Ice Age Floods Expert Vic Baker is interviewed by Nick Zentner (CWU) -Includes Bretz discussion."Five decades of Ice Age Floods research". University of Arizona geology professor Vic Baker visits Ellensburg to discuss his distinguished career devoted to eastern Washington's Ice Age Floods. Several meetings with J Harlen Bretz are also described. |

Vic Baker Interview Vic Baker Interview |