|

|

|

|

|

|

|

THE COLUMBIA GORGE and BEYOND |

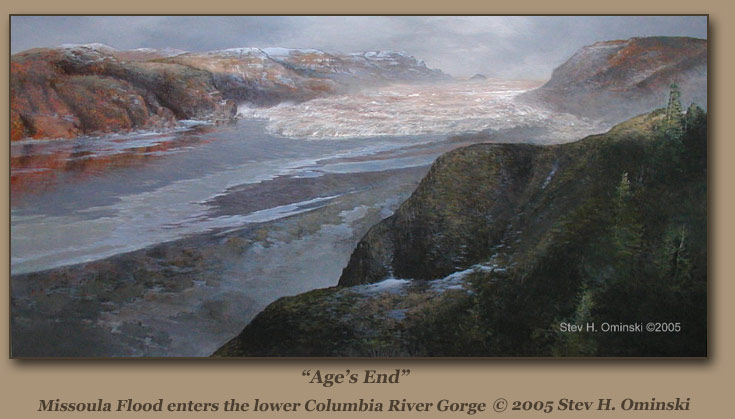

ICE AGE FLOODS ON THE LOWER COLUMBIA RIVER | ||

|

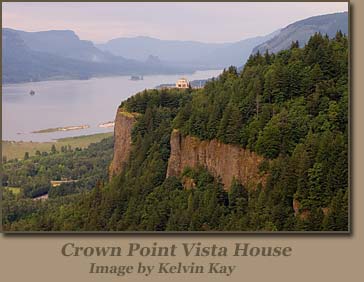

Near the west end of the Columbia Gorge is Multnomah Falls, a 620 foot waterfall that ranks as Oregon’s most-visited tourism attraction. Close at hand is Vista House, an octagonal structure dominated by picture windows that provide magnificent views of the river from its perch atop lofty Crown Point at 733 feet elevation. Multnomah Falls and several neighboring waterfalls are the result of the Ice Age floods, Since the estimated crests of the Lake Missoula floods in this region are in the 700-foot range, a person standing atop Crown Point 15,000 years ago might have enjoyed an awesome view of one of nature’s most powerful spectacles—or might have been merely another casualty. |

| |

|

The Columbia River’s valley from Wallula Gap to the Pacific Coast was deeper than it is today, and the river moved through a V-shaped region whose walls sloped smoothly upward to the surrounding high ground. Since the ocean was lower, the shoreline was about 30 miles west of the modern beaches.

Click above to play Columbia River Gorge video

FLOODING WEST OF WALLULA GAPWallula Gap, south of present-day Pasco, Wash., had stemmed the huge outflows from Lake Missoula, and its restrictions created a temporary impoundment known as Lake Lewis. Below the gap the outflows attained a volume of 40 cubic miles per day. By way of comparison, the highest modern flow on the Columbia is seven-tenths of a cubic mile per day. Another choke point was created as the river valley narrowed in the vicinity of today’s John Day Dam.The backflooding resulted in what geologists call Lake Condon. This choke point also may have retarded outflows from Lake Lewis. Lake Condon’s flood overflows temporarily inundated 1,500 square miles of the Umatilla and Dalles basins. Immediately to the north of the Columbia River [In the state of Washington] the landscape is at substantially higher elevation than on the Oregon side of the river, and the overflooding concentrated in the basins and tributary valleys of the latter state. | ||

|

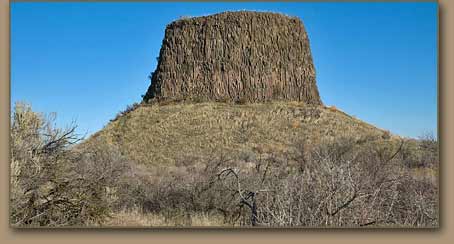

The temporary Lake Condon elevation reached 1,000 feet, and arms of the impoundment backed up through several canyons—Alkali, Blalock, and Philippi—and spilled over into the canyon of the John Day River. The flows demolished basalt outcroppings in the Columbia valley, leaving few prominent features such as Hat Rock east of Umatilla. The extensive scouring process created numerous “kolk” depressions as powerful eddies within the floods wrenched chunks of basalt from the river bed. Stranded “erratic” boulders have been found at the lake’s fringe. |

| |

|

At the site of The Dalles Dam there is an extensive region of well-scoured scablands on the north bank of the river, as well as in the rivers channels. [Dalles often is translated from the French as meaning “gutter”, to describe a narrow channel between cliffs, but the French more commonly used the term to describe places where a steam flows over smooth rocks.] There is another area of scablands to the west of the river after it makes its northward turn. The hillsides between Maryhill and The Dalles show prominent strand lines, and large boulder erratics are located at 800 feet elevation in the vicinity of Maryhill. | ||

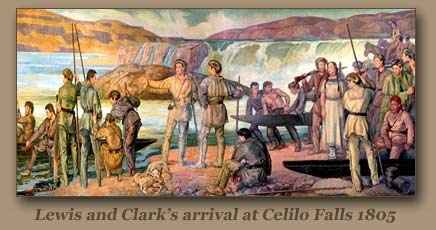

| The construction of Bonneville, The Dalles, John Day and McNary dams has buried many Ice Age Flood features in the Columbia Gorge. [Celilo Falls was inundated by the reservoir waters of The Dalles Dam] | |

In the region generally defined as the Columbia Gorge—from the Dalles to near Crown Point—the Ice Age floods altered the river’s valley from its former V-shaped appearance by scouring the hillsides to a U-shaped configuration. The rock faces lining the channel are more vertical, and waterfalls such as those at Multnomah Falls have vertical drops, where they formerly cascaded at and angle from the ridge tops to the valley floor. Sand and gravel deposits are found up the valleys of side streams, and a large eddy bar is located west of the confluence with the Klickitat River at Lyle, Wash. In the Hood River Valley erratics have been found at 800 feet elevation.

BACKFLOODING INTO THE WILLAMETTE VALLEYWhen the floodwaters cleared the gorge and reached more open terrain, the crests lowered from about 700 feet to 400 feet. But as was the case with Wallula Gap and the narrows at John Day Dam, the waters faced a final choke point at Kalama, about 40 miles north of Portland. This created backflooding through the Willamette Valley as far south as Eugene, Ore. | ||

|

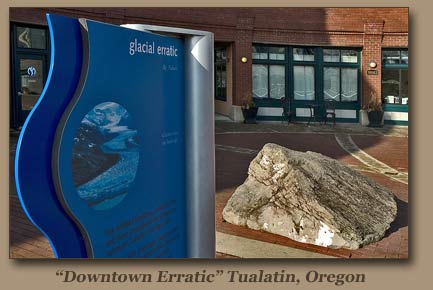

In the Portland area all but the top 250 feet of Mt. Tabor would have been under water. The floods also inundated the Vancouver plains north of the river, encompassing about 275 square miles in present-day Washington. Giant ripple bars are found on the Reed College campus, and mile-long gravel and silt bars occur on the Willamette River between Milwaukie and Clackamas. Numerous kolk depressions dot the region. An area known as the Tonquin Scablands [between Tualatin and Wilsonville] contains patches of scablands and kolk lakes. |

| |

|

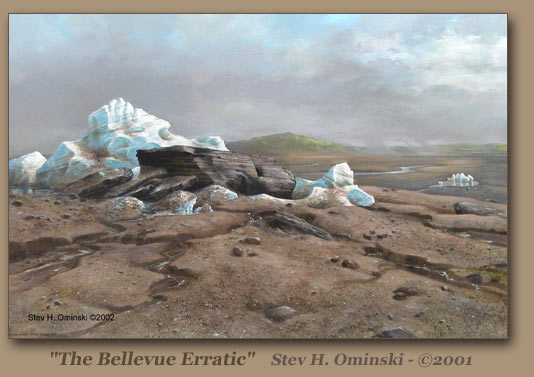

THE BELLEVUE ERRATICAt least 135 groups of erratics have been identified in the Willamette Valley. The largest of these boulders is at Bellevue, southwest of McMinnville. Once reportedly weighing 160 tons, its mass has been reduced to one-half that size by souvenir hunters. [The boulder sits within a small state-owned nature area.]

|

TO THE PACIFIC OCEANWest of the Kalama choke point the flood crests dropped rapidly—to nearly the present sea level at Astoria, and the Ice Age sea level 40 miles west of Astoria. Immense gravel deposits were dumped on the river floor between Kalama and the ocean, and may be as much as 800 feet deep between Astoria and the present seacoast.

|

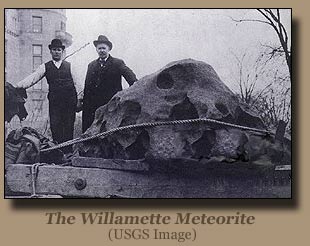

| The Willamette Meteorite The Willamette Meteorite, officially named Willamette and originally known as Tomanowos by the Clackamas Chinook Native American tribe, is an iron-nickel meteorite found in the U.S. state of Oregon. It is the largest meteorite found in North America and the sixth largest in the world. There was no impact crater at the discovery site; researchers believe the meteorite landed in what is now Canada or Montana, and was transported as a glacial erratic to the Willamette Valley during the Missoula Floods at the end of the last Ice Age (~13,000 years ago). It has long been held sacred by indigenous peoples of the Willamette Valley, including the federally recognized Confederated Tribes of the Grand Ronde Community of Oregon (CTGRC). The meteorite is on display at the American Museum of Natural History in New York City, which acquired it in 1906. Having been seen by an estimated 40 million people over the years, and given its striking appearance, it is among the most famous meteorites. In 2005, the CTGRC sued to have the meteorite returned to their control, ultimately reaching an agreement that gave the tribe access to the meteorite while allowing the museum to keep it as long as they are exhibiting it. (Wikipedia source) You can visit a replica on the Willamette Meteorite Interpretive Trail in West Linn's Fields Bridge Park, part of the Ice Age Floods National Geologic Trail that charts the course of the Ice Age Floods.

|