|

During the 1914-1918 period, civic boosters in Wenatchee, led by Billy Clapp, proposed damming the Columbia for irrigation. The concept gained support from publisher Rufus Woods of the Wenatchee World. Meanwhile, Spokane interests promoted a “gravity plan” to transport water from the Pend Oreille River in Idaho to the Columbia Basin via a 130-mile system of canals, tunnels, aqueducts, and reservoirs. The Wenatchee group then called for a smaller dam combined with hydroelectric generators, which could power pumps to lift water uphill from the canyon to the basin’s higher ground. Throughout the 1920s the two groups battled, but neither gained the upper hand.

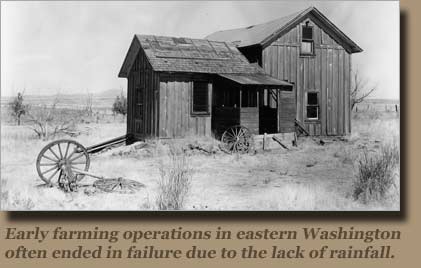

In 1926 Washington’s U.S. senators secured an appropriation for a study of Columbia Basin irrigation, and in 1931 the Army Corps of Engineers issued a report favoring the pumping plan and a dam at Grand Coulee. At that time extreme drought conditions were bringing dust storms and electric power shortages to the Pacific Northwest. The nation was in the grip of a savage economic depression. In 1933 Franklin D. Roosevelt became President.

An advocate of large scale public works projects to stimulate the economy, President Roosevelt was attracted to hydroelectric power. However, the $400 million price tag for the Grand Coulee irrigation project daunted him, and he endorsed a smaller dam for electric power—but one that could be enlarged later. In July 1933 the government approved $63 million for the project, which would be supervised by the Interior Department’s Bureau of Reclamation.

On a Small Scale - Grand Coulee Dam Replicates the Ice Lobe

"It is now proposed to reëstablish the ancient waterway through the great trench of the Grand Coulee. A mere trickle it will be, compared with the river of glacial times. Reinforced concrete will replace glacial ice; and a part, at least, of the west-flowing Columbia will again be detoured southward."

- J Harlen Bretz (1932)

|

Columbia Basin green pea harvest |

CONSTRUCTING GRAND COULEE DAM

|

|

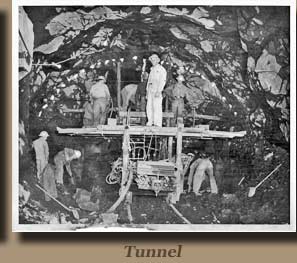

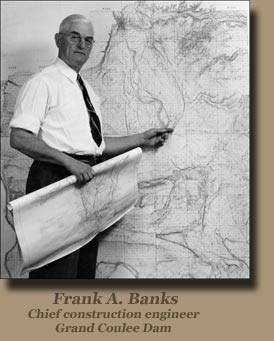

Construction began early in 1934, but within a year’s time the Bureau of Reclamation decided that erecting a future high dam upon the foundation of the low dam posed too many risks of structural defects. The government decided to build the high dam. It proved to be an immense undertaking that would not be completed until 1942.

During the course of the project enough material to fill 60,000 railroad freight cars was delivered, more than 11 million cubic yards of concrete were poured, and 12,000 employees were involved. The dam’s portable gates each weighed 150,000 pounds and the inlet pipes had to be fabricated on-site because they were too large to be transported. A system of conveyor belts and a suspension bridge delivered 700 tons of material per hour to concrete mixing sites. The 108-megawatt turbine generators at that time were the largest ever manufactured.

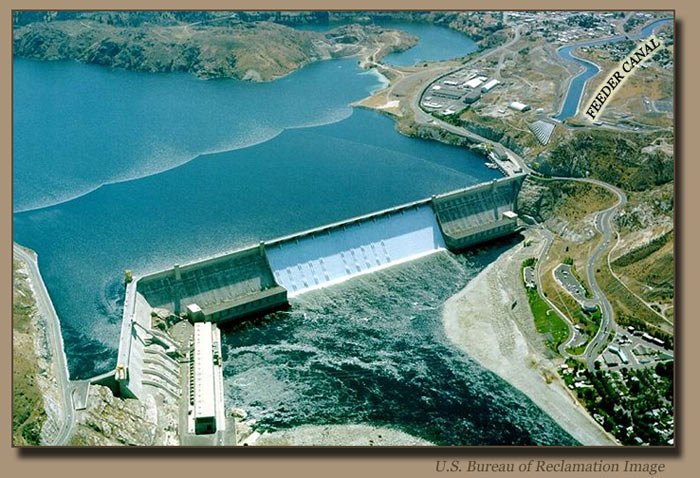

The main dam was completed in January 1942: 4,173 feet in length, 550 feet in height from bedrock, and 500 feet thick at the base. The outlet works consisted of twenty 8.5-foot-diameter conduits whose total capacity was 265,000 cubic feet per second. As of June 1943 project costs totaled $162 million. Electricity from Grand Coulee then moved via transmission lines of the Bonneville Power Administration and served the wartime needs of Pacific Northwest shipyards, metal processing facilities, urban areas and the Hanford Nuclear Project.

|

|

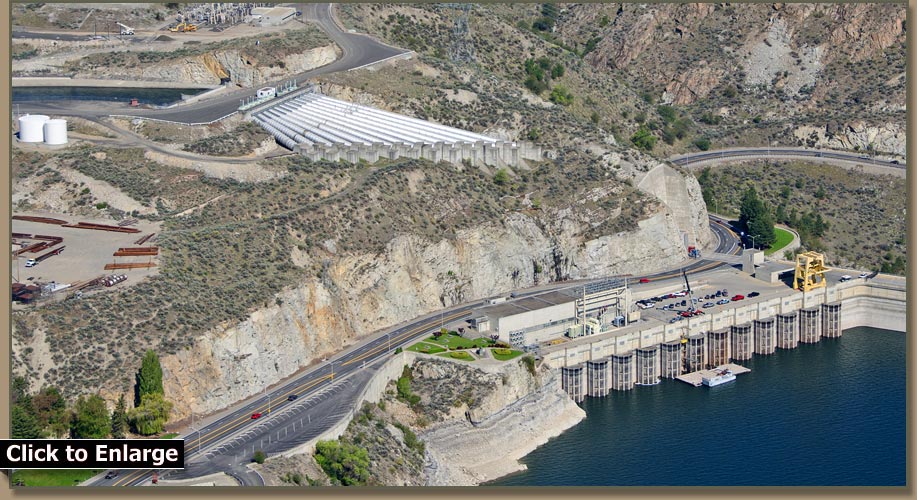

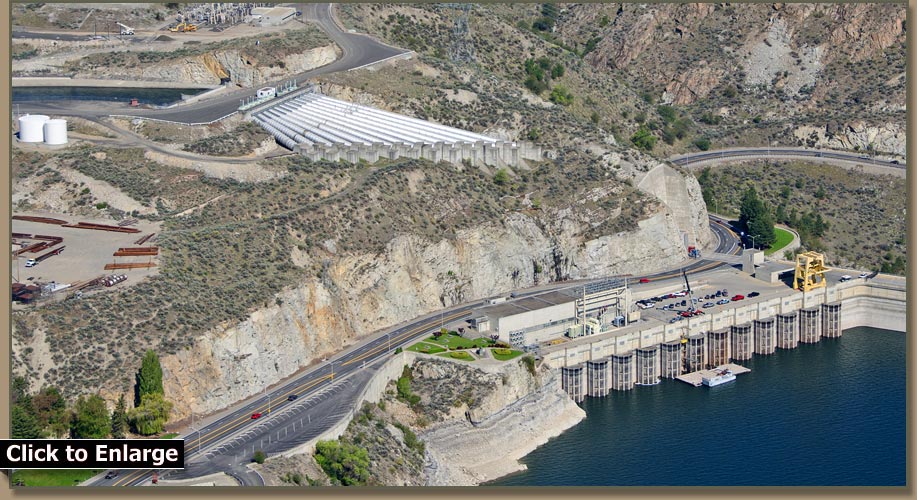

Eventually, the dam was enlarged to accommodate additional power turbines, and the final completed length of Grand Coulee Dam totaled 5,673 feet. The addition of new power generating equipment has brought the dam’s total electric generating capacity to 6,809 megawatts.

During the Ice Ages, parts of the region upstream from the Grand Coulee site had been inundated by Glacial Lake Columbia. After completion of the dam, the waters it impounded were named Lake Roosevelt. This vast reservoir stretches 151 miles to the U.S.-Canadian border, covers 125 square miles of surface area, and holds 9.4 million acre-feet of water.

IRRIGATING THE COLUMBIA BASIN

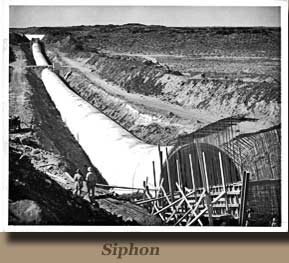

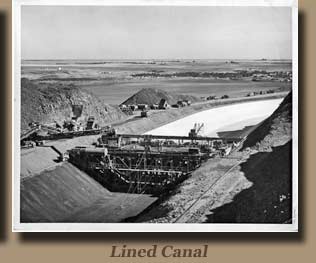

The Pump-Generating Plant at Grand Coulee Dam, pumps water uphill 280 feet from the reservoir behind Grand Coulee Dam to a canal that feeds Banks Lake. Two dams were built 27 miles apart in the Grand Coulee to hold irrigation water (Banks Lake). The system allows water to flow either direction in the feeder canal as the reversible pumps at the pumping station are also designed to generate power when demand is high. |

|