|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Glacial Lake MissoulaThe glacial lake, at its maximum height and extent, |

|

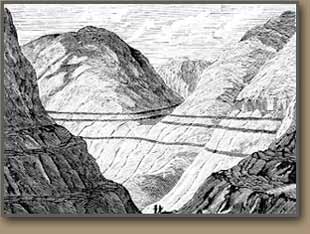

Mission Valley view - Glacial Lake Missoula interpretive display at National Bison Range - Moiese, Montana. - Artwork by Byron Pickering - |

|

Lake Missoula strandlines (Strandline: "a shoreline above present water level" -Webster) are etched into the hillside behind the University of Montana's Main Hall. Geologists believe the site of present-day Missoula was under about 950 feet of water during the largest lake fillings. |

FIRST TO RECOGNIZE CLUES LEFT BY AN ANCIENT LAKE |

|

|

|

As far back as the 1880's, geologists believed that an immense body of water once occupied the deep mountain valleys of western Montana. Lake Missoula expert David Alt (geologist/author) believes the first mention of Lake Missoula shorelines was recorded by geologist T.C. Chamberlin in 1886. During a late summer mapping trip through the Mission Valley, Chamberlin noted faint "watermarks" on the surrounding hills. Chamberlin had read reports describing Scotland's "Parallel Roads of Glen Roy" and correctly interpreted the Missiona Valley lake features. It wasn’t until the 1960's that scientists began to accept the idea that catastrophic floods from Montana were responsible for radically altering the landscapes of eastern Washington. | ||

- Please view at least the first 10 seconds of BBC video above -"So while Chamberlin easily identified the old shorelines, they were tangential to his main duties. The summer was almost over, so he did not pursue the subject. It waited for J.T. Pardee." - David Alt |

|

|

During tens of thousands of years of cooler and wetter climate in North America, huge ice sheets periodically spread southward and then gradually retreated. The final onslaught—known as the Wisconsin glaciation—brought masses of ice to the river valleys of northern Montana, Idaho and Washington. Meanwhile, alpine glaciers formed at the region’s higher elevations. | |

| |

|

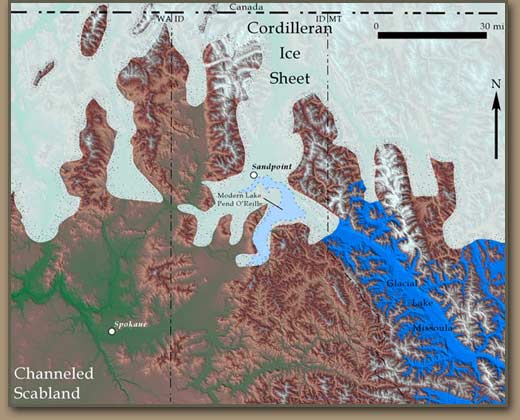

Glacial Lake Missoula impounded behind "Ice Dam". Another blockage occured to the west where the Okanogan Lobe plugged the Columbia River's course creating Glacial Lake Columbia (body of water with a 500 square mile surface area - at maximum fill). Glacial Lake Columbia strandline image lower on this page. |

Glacial Lake Missoula shown southeast of ice dam. City of Spokane noted on map. Modern-day Lake Pend Oreille shown covered by ice lobe ("ice dam"). |

Ice Dam Blocks |

| |

|

The Clark Fork’s drainage area includes a network of valleys hemmed in by high mountain ranges. Lake Missoula is named for the Montana city which occupies a central location in the Clark Fork watershed. Missoula’s nearby mountains also contain graphic evidence of the lake’s existence. Given the climate conditions of 20,000 years ago, precipitation and glacial meltwater from most of western Montana’s mountainous regions would have ended in Lake Missoula. At its largest extent, Lake Missoula’s depth exceeded 2,000 feet and may have held 600 cubic miles of water—as much as Lake Erie and Lake Ontario combined. The surface area covered 3,000 square miles and the shoreline attained an elevation of 4,200 feet. In addition to the Clark Fork Valley northwest of Missoula, arms of the gigantic lake extended south through the Bitterroot; east to near Deer Lodge, Mont.; and north through the Flathead, Thompson, Mission and Clearwater valleys. Ice Age Lake Missoula probably was a scenic locale, but it also would have been a somewhat forbidding place. The water was deep, dark and murky with sediment. There is no evidence of fish, and scientists speculate that sediment known as “rock flour” [because it was ground down to powder by glacial action] created poor habitat for both fish and the aquatic life-forms that would have nourished them. Alpine glaciers would have intruded upon Lake Missoula’s shores. Although mammoths, mastodons and bison likely roamed the nearby areas, there is no direct evidence of the presence of human beings. This unfriendly environment for living things was made even worse by the fact that Lake Missoula emptied in dramatic fashion dozens of times over a several thousand years — perhaps as often as once every 50 years or so. | ||

GEOLOGIST DISCOVERS THE WATER LEFT IN A HURRY | |||

|

Once geologist J. T. Pardee realized the small rolling hills or ridges on Camas Praire were actually giant current ripple marks - he determined they could only have been formed by powerful currents of fast-flowing water. The huge lake had emptied suddenly! Pardee’s new information was presented in 1940 and published in 1942. |

View Larger Map Navigate with Google Map tools to explore Giant Current Ripples on Camas Prairie. |

|

David Alt's book is an excellent resource for anyone interested in exploring Lake Missoula features. |

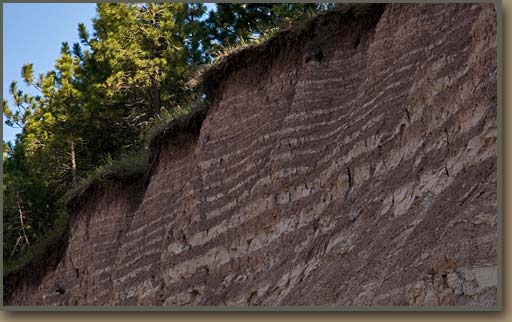

Geologist David Alt interprets light bands as river silts and dark bands as glacial lake sediments. |

|

|

|

| |

Ice Age Floods Institute field trips are a great way to learn about Glacial Lake Missoula and the Ice Age Floods |

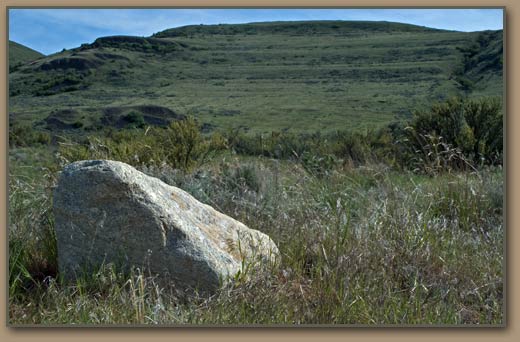

Bedrock was ripped apart in some areas as the lake drained. Angular boulders did not travel far before settling out of flow. | |

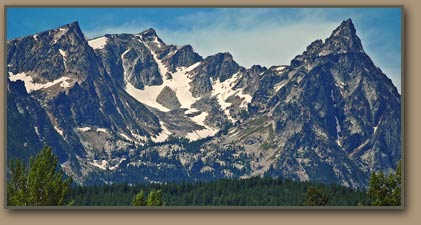

Bison grazes at National Bison Range near Moiese, Montana. Mission Range in the distance.

|

|

THE ICE DAM GIVES WAY | |

|

Scientists don’t completely agree on the precise sequences or nature of actions that led to the periodic failures of the Lake Missoula ice dams, but several general principles contributed to the event.

|

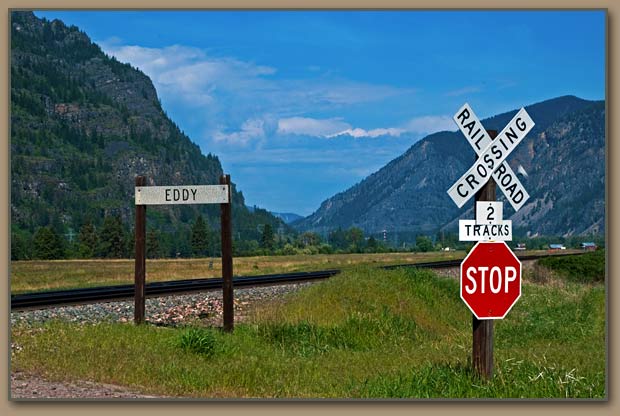

Eddy Narrows

|

|

The pressure of water against the ice dam’s base, coupled with any dams tendency to suffer minor leakage, probably caused a weakening of both the dam’s base and the rock and other material immediately beneath it. Meanwhile, the dam itself was being tugged upward by its natural buoyancy, since ice is lighter than water. At some point the dam was breached, probably through a combination of undercutting by water and multiple fractures of the ice mass itself. Whatever happened, it wasn’t a minor break. Enough ice was bashed out of the way in a very short period of time to make room for a flood torrent whose volume has been calculated at 8 to 10 cubic miles per hour—a rate that amounts to 10 times the combined flows of all the rivers on the planet Earth. Eventually the failed ice dam would be replaced by a new one as the Purcell Valley glacial lobe continued its southward extension. This process was repeated until the glaciers finally retreated northward. | |

LAKE MISSOULA’S CATASTROPHIC FLOODS | |

|

The cycle of floods that reshaped the landscape from the Idaho panhandle all the way to the Pacific Ocean represented a series of events—each one of them ranking as one of nature’s truly catastrophic occurrences. Many scientists believe that about 40 catastrophic floods originated at Lake Missoula. Others believe the number could be substantially higher. There is evidence of flood episodes from other sources during the same period—glacial Lake Columbia, for example. There are indications of flood events at much earlier times during the Ice Age. Since subsequent glaciation and flooding would have obliterated evidence, we may never know for certain. |

|

- An eyewitness to one of these events would have been terrified -Depending upon the viewer’s vantage point, the oncoming torrent would appear as a huge wave from 300 to 1,000 feet high. Actually, it would look more like a cross between a wave and a mudslide because the flood would be carrying tons of earth, boulders, chunks of ice, trees and any other moveable debris that got in the way. Depending upon the location, the torrent could move at a speed ranging between 30 and 80 miles an hour. The noise would be deafening. THE FLOODS’ PATHWAYSOutflows from Lake Missoula raced southward down the Purcell Valley and then made a right turn through Rathdrum Prairie and headed for the site of present-day Spokane, Wash. There it would have encountered the eastern extensions of another body of water—Lake Columbia. The Lake Missoula torrent would have filled Lake Columbia to overflowing, while at the same time it continued to race through the landscape of eastern Washington—carving flow channels as it traveled. The initial Lake Missoula flood would have begun the process of reshaping the terrain of eastern Washington. Subsequent floods would have continued the process but generally would have followed the pathways established at the beginning. These floods, which are known as “scabland” floods because of the unique terrain features they created, were concentrated along three routes.

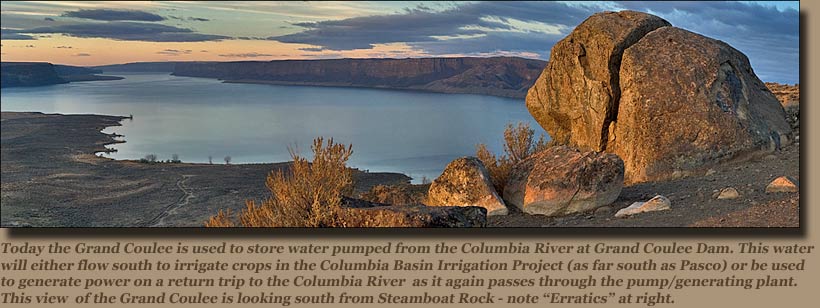

The tremendous volume of water collecting in the Pasco Basin overtaxed the capacity of the Columbia River’s channel through Wallula Gap to handle it. A temporary impoundment—known as Lake Lewis—filled to depths nearing 900 feet in the Pasco Basin for several days until this “retention pond” drained. The Columbia Gorge created another choke point, which resulted in Lake Condon, another temporary impoundment. A final series of obstacles west of Portland caused extensive backflooding into the Willamette Valley. THE FLOODS’ IMPACTAlong the floodways more than 50 cubic miles of earth and rock were removed and deposited downstream. The rich Palouse soils were scoured to depths as great as 250 feet, and prime farmland was transformed into scabland. Gravel bars, some of them 400 feet high, were created. Large boulders carried by ice rafts were deposited hundreds of miles from their origins—as far as Oregon’s central Willamette Valley. Much of the eroded material was carried all the way to the Pacific Ocean, where extensive deposits of flood sediment have been found hundreds of miles from the mouth of the Columbia River. The most prominent visible remains of the late Ice Age Floods are the Channeled Scablands of eastern Washington. The scabland region dominate a huge tract of the central Columbia Basin, although in the northeastern sections scablands are intermixed with higher hills on which the rich Palouse soils survived the floods and today are valuable cropland. In the region’s valleys the floods scoured everything down to the upper basalt layers—and even dislodged huge chunks of basalt. This led to further erosion from later floods. One result was the creation of numerous lakes, ranging from small ponds to larger impoundments such as Sprague Lake and Rock Lake. The scablands also featured numerous buttes, knobs, and other basalt projections. The most visually impressive scabland area is the Drumheller Channels, where floodwater spilled southward out of the Quincy Basin.

The Grand Coulee is a remarkable legacy of the Ice Age floods

|